Conclusions and Recommendations

This collection of essays has sought to provide a platform for a range of different views about some of the most challenging debates in human rights and peace building. It…

This collection of essays has sought to provide a platform for a range of different views about some of the most challenging debates in human rights and peace building. It does not make any claim to be exhaustive or definitive, indeed there are many important perspectives that will need to be part of future work, but it does attempt to be a starting point for conversations about the competing rights and responsibilities at play in this challenging area. It also seeks to remind all parties to the conflicts and the international community at large that all people have human rights irrespective of where they live.

Neither the editors of this publication nor their respective organisations, the Foreign Policy Centre (FPC) and the Norwegian Helsinki Committee (NHC), are endorsing any views on the intractable issues of status set out by a number of the other essay contributors. However, it is important that local voices are heard, while recognising and understanding that their positions can be painful to hear for those from the states from whom they are trying to formally separate and particularly for those from internally displaced persons’ (IDP) communities whose lives have been changed irrevocably by the conflicts that forced them to flee. Nevertheless, the issues around status remain intractable at an intergovernmental level and the subject of much substantive research by peacebuilders and academics that we do not attempt to replicate here. It is with that in mind that the conclusions that we attempt to draw here and the suggested recommendations for action look to proceed as much as is possible, given the challenges of doing so, from a status-neutral position.

At the heart of this debate is the question of whether and how the international community should engage with the de facto authorities, local civil society and civil society. Georgia, Azerbaijan and Ukraine in particular[1] robustly defend against any initiatives that would be seen to lend credibility to the de facto authorities or their policies. As a result, engagement on these issues by international governments and institutions from the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) to the European Union (EU) is couched in terms of reiterating and reinforcing the parent state’s position on territorial integrity. The de facto authorities in turn similarly robustly defend their own claims to independence and regularly reject initiatives and attempts at international monitoring that seek to assess the situation in the breakaway regions formally as part of the international community’s work in the parent state. For example, efforts by the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council and special rapporteurs to visit Abkhazia and South Ossetia as part of their mandate investigating the situation in Georgia have been rejected a number of times.

Recent efforts to change facts on the ground that only create further challenges on the issue of status, such as the attempts at ‘borderisation’ through barbed wire fences and other means, between both South Ossetia and Georgia and between Abkhazia and Georgia, risk undermining the human rights of people living in or near the Administrative Boundary Lines (ABLs). Such changes create specific challenges for members of the two disputed territories’ Georgian communities and those living in Georgian controlled territories. Stopping ordinary people from physically crossing the ABLs or making it more difficult for them to travel by preventing them from getting the relevant documents both impinges on their human rights and undermines efforts at confidence building that would be a necessary part of any path to conflict resolution. The Government of Georgia may also want to consider however that particularly in Abkhazia the inability of the de facto authorities to build their own capacity, partially as a result of international pressure, has led to an expansion in Russian control and influence beyond what would have been desired by many in the local power elites.

In this essay collection a number of different authors make suggestions for engagement to address both human rights challenges and to build local capacity to address every day needs, some of which are more status neutral than others. While these are all worth considering on their own merits the editors wish to narrow the focus of our conclusions overall to three areas: engagement with civil society such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), journalists, lawyers and other non-state actors; access to international law; and the rights of national minorities and IDPs.

Civil Society

This collection has made clear that finding ways to engage with and support local NGOs, journalists and lawyers to learn, strengthen and push back against those that would curtail their activities are central to efforts to improve human rights in unrecognised states. International NGOs and donors can face a significant challenge in making contact with their counterparts in de facto states through a mixture of bureaucratic hurdles, political pressure and legal restrictions or sanctions by both status conscious ‘parent’ states and wary de facto authorities. Physically getting access to de facto states can be challenging, particularly for those seeking to do so in a manner that doesn’t antagonise the parent states (accessing the de facto states from Georgia, Azerbaijan and Ukraine rather than the quicker routes via Armenia and Russia). Azerbaijan has been known to blacklist people that have visited Nagorno-Karabakh via Armenia without permission and organisations that do not follow the procedures set out by Georgia and Ukraine will face a significant backlash that would create problems for their work in those countries. In his essay Anton Nemlyuk specifically called on Ukraine to find ways to request permission to access Crimea remotely and if possible find ways to allow permission for access via Russia rather than Ukraine’s land border, while the NHC and others have called for greater flexibility from all parties to facilitate people-to-people contact both to allow status-neutral field research and to work directly with local counterparts.

Access issues include attempts to restrict the international funding of NGOs by the South Ossetian (and of course Russian) foreign agents laws, Transnistrian legislation on reporting requirements and funding approval by the Coordination Council of Technical Aid[2], as well as other official and unofficial pressures from the parent state against local NGOs collaborating with international groups. The precarious legal and security situation facing the de facto authorities, as well as Russian pressure in a number of cases, is a key factor in the wariness towards international collaboration. However, given that these de facto administrations regularly call for international engagement, the EU and international governments need to be proactive in defending the right of international civil society to gain access. Efforts at improving access for human rights NGOs will of course sit alongside similar efforts to defend Track-2 peacebuilding initiatives, with efforts to improve human rights potentially creating more space for honest and open dialogue on conflict issues.

A range of different types of civil society engagement that would be beneficial have been suggested throughout this publication. These include supporting independent reporting and newsgathering efforts to draw attention to the activities of the de facto authorities, improving awareness and accountability amongst the residents of the de facto states, within the public and elites of their metropolitan state patrons, ‘parent’ states and to the international community. There are also calls to back efforts that bring together lawyers, journalists and NGOs to encourage collaboration. Such collaboration is believed to be important in addressing human rights issues, disseminating knowledge about human rights and building pressure on authorities (de facto and de jure) to address issues. This work could be through joint trainings, ad hoc collaboration or assisting with the development of more structured, though still informal, associations to help build networks and trust.

Donors, whether philanthropic or governmental, need to be clear that though targeted funding at groups unlikely to receive local support can be helpful, skill sharing and helping give a platform for local voices is also important. This is because particularly in the cases of South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Transnistria and to a lesser extent for Nagorno-Karabakh any financial or economic incentives the international community might be able to bring to the table will be dwarfed by the scale of financial transfers being provided by Russia or to some extent by Armenia and its diaspora communities. As Thomas De Waal points out, as part of a recent study of a number of unrecognised entities, in Abkhazia ‘Moscow’s spending on pensions alone was more than ten times the EU’s aid program in 2008–2016.’[3]

Efforts to directly improve the performance of the de facto human rights ombudspeople, while potentially beneficial, would face significant hurdles for international governments or international institutions. There may however be space to strengthen the capacity of local NGOs and lawyers to improve their abilities to influence and where necessary push back against de facto agencies and bodies, empowering people and reducing the power imbalance between them and the de facto institutions rather than empowering the institutions themselves.

A number of contributors have argued in favour of finding ways to improve the provision of public goods such as health care, education, social services, youth provision, and housing to improve the wellbeing of local people. However, if the de facto authorities are the ones providing the service there is a significant challenge that capacity building efforts even in these areas would be seen as enhancing their capacity to govern and therefore not be status neutral. A possible alternative might be to find ways to expand the capacity of local civil society to deliver such services, so that in theory such provision could continue irrespective of who controlled the area.

Accessing international law

The second main dimension for protecting people’s rights is through international law, and while international bodies may set challenges for the de facto authorities[4] ultimately the rights and duties flow through and reinforce the importance of the recognised states who are signatories to the relevant treaties. A number of essays but particularly that by Ilya Nuzov show the importance of applying international law, particularly the European Convention on Human Rights to abuses committed in the breakaway entities. As set out above improving capacity of local lawyers working on the ground in the de facto states and in the border and IDP communities impacted by the conflicts, improving technical expertise and legal knowledge is a vital first step. However, it is also essential to help support lawyers in the metropolitan states (Georgia, Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Moldova) who are able to take cases of abuse and seek remedies through the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

Both improved legal documentation and other information gathering efforts may open up opportunities for ‘Global Magnitsky’ type legislation in a number of important international jurisdictions including the US, UK and the Baltic states that could target the international assets of local human rights abusers and their enablers in the governments of occupying powers. Similarly, such documentation may help facilitate cases in third country courts operating under universal jurisdiction to holder abusers to account. Donors need to consider how they can best assist with supporting efforts to access the ECtHR, courts of universal jurisdiction and to trigger international sanctions.

As the NHC have set out in their essay earlier in this publication both the patron and the parent state as well as de facto authorities have a responsibility to respect, protect and fulfil human rights to the extent that they have effective control over a territory. They should co-operate in facilitating access to international human rights mechanisms and in the implementation of international decisions. While ‘parent states’ can be challenged over ways in which they may be inflexible in their approach, the ultimate responsibility for allowing access by international human rights mechanisms lies with the de facto authorities and their international patrons. Failure to provide access to monitoring by UN, OSCE and Council of Europe human rights mechanisms will continue to be seen as a sign of defensiveness about local standards, undermining international perceptions of the de facto authorities’ capacity to effectively provide governance to the areas under their control.

Minorities and IDPs

Protecting the human rights of minority communities within the areas controlled by de facto authorities is not only one of the most important areas for improving human rights standards in these areas but will be an essential component for any future peace process or discussions on status. Whether future paths on status lead towards reunification, independence, annexation[5] or perpetual limbo, the credibility of the de facto authorities and occupying powers will be judged by the international community by how they treat minority groups who live in the territories they control. In the case of Abkhazia, however one defines the issue of status, the challenges facing members of the Georgian community in the Gali region will continue to be particularly sensitive and practical steps to improve the situation for the local population are urgently needed.

The IDP dimension has been less of a focus for this publication given other work in this area but it remains no less important. There is more that the international community can do to raise awareness of the continuing plight of IDPs in Georgia, Azerbaijan and Ukraine, particularly those whose future remains uncertain. This can include more concerted efforts to improve financial and technical support through the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other mechanisms, and ensuring that issues around protecting the property rights of IDPs pending any agreed peace settlement remain a core dimension of any international dialogue with the de facto authorities.

Recommendations

To the de facto authorities and recognised state governments

To the International Community and Global Civil Society

Authors' bios:

Gunnar M. Ekeløve-Slydal is Deputy Secretary General, Norwegian Helsinki Committee, and a Lecturer at the University of South East Norway. He studied philosophy at the University of Oslo and worked for many years for the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights at the University of Oslo and as Editor of the Nordic Journal on Human Rights. He has written extensively on human rights, international institutions, and philosophical themes, including textbooks, reports, and articles.

Adam Hug became Director of the Foreign Policy Centre in November 2017. He had previously been the Policy Director at the Foreign Policy Centre from 2008-2017. His research focuses on human rights and governance issues particularly in the former Soviet Union. He also writes on UK foreign policy and EU issues.

Ana Pashalishvili is a lawyer with a broad spectrum of expertise in international law and human rights. She joined the NHC in April 2014 and since then has been actively working on topics related to human rights, international public and criminal law as well as data privacy, documentation and project management.

Inna Sangadzhieva is a Senior Advisor at the Norwegian Helsinki Committee (NHC). She is a linguist from the Kalmyk State University (Russia) and has MA at political science from the University of Oslo. Inna has been working at the NHC for 15 years, she is an author of several articles and reports, mostly regarding the political and human rights situation in Russia and the former Soviet Union.

Photo by Lene Wetteland, Norwegian Helsinki Committee

[1] The Moldova-Transnistria situation is somewhat more fluid and flexible, albeit that status issues do still pose major challenges.

[2] Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2019: Transnistria, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/transnistria

[3] Recent works by authors such as Thomas De Waal and the International Crisis Group have set out ideas for status neutral engagement in a range of different spheres that stretch beyond the human rights focus of this publication. For example https://carnegieeurope.eu/2018/12/03/uncertain-ground-engaging-with-europe-s-de-facto-states-and-breakaway-territories-pub-77823

[4] For example as noted by Ilya Nusov ‘Resolution 2240 on access to ‘grey zones’ by CoE and UN human rights monitoring bodies, the Parliamentary Assembly of the CoE (PACE) considers that: the exercise of de facto authority brings with it a duty to respect the rights of all inhabitants of the territory in question, as those rights would otherwise be respected by the authorities of the State of which the territory in question is a part; even illegitimate assumption of powers of the State must be accompanied by assumption of the corresponding responsibilities of the State towards its inhabitants.’ http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-EN.asp?fileid=25168&lang=en

[5] In the case of Crimea Russia has already taken this step but at present it seems unlikely that the international community is willing to acquiesce to Russian demands for recognition of its annexation in the near future.

[post_title] => Conclusions and Recommendations [post_excerpt] => [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => conclusions-and-recommendations-3 [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2019-09-26 09:09:23 [post_modified_gmt] => 2019-09-26 09:09:23 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://fpc.org.uk/?p=3982 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [1] => WP_Post Object ( [ID] => 3935 [post_author] => 38 [post_date] => 2019-07-25 03:00:35 [post_date_gmt] => 2019-07-25 03:00:35 [post_content] =>Brexit is an attempt to tackle domestic problems by altering our relationship with our European neighbours. Some feel that this is doomed to fail because our economy and security is so integrated with our neighbours and we should therefore concentrate on avoiding it or getting the least-worst option while tackling with renewed vigour the discontents – about housing, unstable jobs and incomes, and rapid cultural change which brought this populist wave. Others believe that through the projection of a ‘Global Britain’ we can rebuild our prestige and renew our international relationships. But what if the domestic discontents are part of the unfolding of international developments?

After all, Britain is not the only European country facing tough economic competition from the Far East; or large-scale immigration; or the pressure on its youth from an apparently ungovernable internet and social media. And if this is the case, what does it mean for the way we conduct our foreign policy?

This essay aims to look at three things: the nature of the modern world, what we want to achieve in it and thirdly at the levers we can pull and the resources we can bring to bear to achieve our aims.

The Modern World

Interconnectedness beyond national boundaries is not a new phenomenon. Once England was part of the Roman Empire, then we were ruled from Scandinavia; even as the Kingdom united and grew we were part of the Roman Catholic Church. Later we became a phenomenally successful trading nation with an Empire which stretched across the globe bringing cultural as well as financial exchange.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the proportion of our economy which is traded remained constant between 1900 and 2000. In 1900 exports constituted 24.9 per cent of the economy and in 2000 it was back at 24.9 per cent. But the degree of interconnectedness today seems far more immediate and intense – at the click of a button we can be in touch with people thousands of miles away; huge movements of people flow – some motivated by economic opportunities, others forced by war, desperation and climate change.

We in the UK are fortunate for the last 75 years to have lived in a largely peaceful and prosperous environment. This is frequently attributed to the very successful institution-building in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War (WWII), in which we played a significant part: the United Nations (UN), the UN Declaration of Human Rights, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and the economic institutions – the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (to which we had recourse ourselves in 1976), the World Bank, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade(GATT) which developed into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) - and, of course, the European Union (EU).

One of the high points in this period came on 9th November 1989. I can remember watching the TV coverage of the crowds breaking the Berlin Wall and writing in my diary – “this is the most important day of my life.” Those were heady days, to be young was very heaven. It felt like the completion of the liberation of May 1945. The bipolar world and the threat of nuclear war, which that had meant, was lifted. We were certain we could be safer, and some of us on the Left looked forward optimistically to the development of new economic models, negotiating a path that would take seriously the Eastern European commitment to equality and the West’s enterprise and openness. Russia was invited to the G7 meetings in London. We discussed the possibility of using co-ops and the Yugoslav model.

However Yugoslavia was the first country in the 1990s to collapse in a bloody and violent war; refugees from its horrors began arriving in London and we were shaken from our optimism.

The political right claimed victory – market liberalism was declared to be the both the cause and the destination of this new world – the alpha and the omega – even in China Deng Xiaoping was following its tenets.

Again, of course, their confidence was overblown. The rise of religious fundamentalism – of Islam as a political force in the Middle East and Christian Evangelicals in the US – pushed back against the idea or possibility of one totalising ideology.

The advent of climate change and the collapse of the markets in 2008 show both that we have not achieved a secure and sustainable way of life and that developments across the globe affect our day to day lives. Badly regulated US mortgage markets means queues outside Northern Rock; the destruction of the Amazon rainforest brings floods in Cumbria.

Following the Brexit vote, there has been a lot of soul searching about the failures of domestic policy – why were those outside the major cities feeling particularly disempowered? Why were some of those with the most to lose from rupturing economic relationships with Europe amongst some of the most inclined to vote Leave? But not so much attention has been paid to international policy.

The fact is that the world in 2019 is not as it was in 1945 – or indeed 1913 or 1989. Yes, we are not in a bipolar world, but nor are we in a world which can be dominated by the Americans.

The biggest international story is the rise of China. Forty years ago, China was a struggling middle-sized power with a poor, inefficient and stagnant economy. Since the implementation of major economic reforms in 1979, it has experienced a staggering economic transformation. According to the World Bank, China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth has averaged nearly 10 per cent a year—the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history.[1] It is now the world’s second largest economy as measured by nominal GDP and has established itself as a geopolitical superpower.

The other big story is the emergence of the other BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). First conceived of in 2001 by Goldman Sachs during an economic forecasting exercise, the BRICS together contain three billion people – over one third of the world’s population – and account for between 25-30 per cent of global GDP.[2] The grouping has evolved from a popular concept to a formal grouping – holding their first summit in 2009 – and present a direct challenge to the hegemony of the G7 nations.

Progress on human well-being paints a mixed picture. On the one hand, we have seen a discernible improvement in people’s lives over the past three decades. According to the UN Development Programme (UNDP) data, between 1990 and 2017 nearly every country in the world (with a few notable exceptions, such as Syria and Yemen) has seen a net increase in their Human Development Index (HDI) scores and life expectancy.[3] World Bank Data also indicates a continued (albeit slowing) decrease in poverty levels, with the percentage of people living in extreme poverty globally falling to a new low of 10 per cent in 2015.[4]

On the other hand, there is plenty to overshadow this progress. According to the UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, the number of people fleeing war, persecution and conflict exceeded 70 million in 2018.[5] This is the highest level that UNHCR has seen in its almost 70 years. There is also still plenty to be done on human rights and democracy. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights turned 70 in 2018, yet in the past two years alone, we have seen nearly 700,000 Rohingya Muslims forced to flee state oppression in Myanmar, over one million Uighur Muslims detained in re-education camps in Xinjiang and over 300 human rights defenders have been murdered.[6] According to Freedom House, 37 per cent of the world’s population live in countries categorised as ‘not free’, and out of a possible score of 100, two thirds of countries scored less than 50 on the Corruption Perception Index (CPI).[7]

Britain may have thefifth largest economy today, but the inexorable rise of the emerging economies with larger populations could see us drop down to 10th in 2050, behind Indonesia and Mexico.[8] This is simply not under our control. This is not to say we cannot adopt both domestic and foreign policy stances which are positive and constructive - we can. But as the psychotherapists say: the art of growing up is coming to terms with the world as it is, not as we would like it to be.

These big prospective changes also explain why countries beyond the victors of the Second World War are discontent with the governance arrangements of the existing institutions – why, for example, China set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank to rival the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD- part of the World Bank Group) and why there are calls to expand the UN Security Council.

But it’s not just a question of whether the right people are sitting at the table. An even bigger question is whether we have the right institutions tackling the right problems.

The Bretton Woods institutions were far sighted and strong, but they were established to tackle the world’s problems in 1945 and as we have seen, these are changing. Let me give some examples: the internet; climate change; the impact transnational corporations have on human rights; drugs; migration and the rights of refugees.

We are often enjoined to defend the rules-based international order and explain its benefits and virtues. This is usually in response to a populist attack from President Donald Trump. President Trump is particularly irritating, because he is good at identifying actual weaknesses – Chinese theft of intellectual property or European countries’ failure to pay a fair share of NATO costs – which no one can deny, while at the same time proposing solutions which are totally counterproductive: a trade war or US disengagement from a shared defence alliance.

So it is true that the UN has been much stronger than the League of Nations in providing a forum for resolving disputes peacefully and that the WTO has, up until now, prevented the ‘beggar thy neighbour’ policies which dogged economies in the 1930s, but it’s also true that big issues like how to govern the internet and tackle climate change effectively have not been cracked. And that, especially post-2008, a sense of insecurity has brought to the fore strong men – Trump, Putin and Ji and right-wing populists – Matteo Salvini and Viktor Orban whose proposals are to build up walls, whether physical, legal or metaphorical, against outsiders.

Brexit is our own special national brand of populism. This then is the hostile environment in which we are seeking to tackle our problems.

What do we want to achieve in our Foreign Policy?

Citizens regard the first duty of government as being to provide security and stability. This does not of course mean that foreign policy needs to be an exercise in crude nationalism such as ‘America First.’ There is a huge appetite for policies which bring security and stability but are also socially responsible.

Two points are worth making here. Firstly, security and social responsibility are not necessarily in conflict. We can afford to spend two per cent of our national income on defence and 0.7 per cent on overseas aid; we can share our intelligence resources with our NATO allies and run a BBC World Service which broadcasts truthful fact-based news into closed countries like North Korea. We can do both. Secondly – and it flows from this socially responsible policy framework – promoting development and tackling climate change effectively will increase our security, because they will increase the security of others and promote a shared worldview.

Emily Thornberry spoke at length about this to the Institute for Government recently: “[We should] champion certain values as well as commercial interests” and “by putting values back at the heart of our diplomacy [we will] help to transform what Britain is seen to stand for as a country.”

And Jeremy Corbyn has said “Labour will speak for democratic values and human rights” and “will be driven by progressive values and international solidarity”[9]

Whatever the rights or wrongs of the misadventure of Iraq – it clearly did not make the British people more secure.

So we want to pursue security, stability and social responsibility.

The prime security alliance the UK enjoys is through NATO – itself based on shared interests and values.

Key to this for us has been the US-UK ‘special relationship’, and this has been put under considerable pressure lately. Firstly by revulsion among the public at the aftermath of the Iraq War; then by the election of Trump who seems to embody most of what the British Left dislikes about the US and little of what it does like, and finally by Brexit – which potentially means that when the US want to contact Europe the first phone they ring is no longer going to be the one in King Charles Street.

What this tells us is not that we no longer share objective interests with the US or that our strong cultural and historic ties are worthless – but that, perhaps like a marriage that’s gone through a bad patch, the relationship needs a bit of work. It’s not going to be what it was, so we need to find a new balance. An interesting study recently published by the UN Association[10] looking at international perceptions of the UK found that a relationship in which the two countries are seen as too close reduces our prestige. If we merely follow the US – there’s no point in anyone asking for our help in influencing them.

Labour is committed to NATO membership and the two per cent and this essay is not about defence policy but refashioning the relationship so it is positive without being subservient on trade (chlorinated chicken) or culture (our children shouldn’t be exposed to bad cartoons. Britain has much higher standards for children’s television than the US, with less violence and more rounded and diverse characters. The US film moguls would like to swamp our TV stations). This is not about Brexit, but it is worth noting that the current government as part of its Brexit preparations has increased the number of diplomatic positions in European countries by 50.

This of course is part of a more general re-focussing which will be required if we leave the EU. An assessment and review of the impact and significance of the change means working that bit harder to be heard elsewhere.

Individual bilateral relationships matter. But I hope just two examples will illustrate that alone they cannot deliver our aims.

China is a global power and as we have noted it is growing rapidly. But the truth is we are conflicted. We want and need the trading opportunities offered, this will help our economic stability, but this is tempered by our concerns over Chinese political culture and human rights record. We look for opportunities to co-operate – like climate change - but sometimes the conflicts become sharp - as when we look at developments in Hong Kong or investment from Huawei. These bring into relief, as it were, the dilemma. Could we hope to persuade the Chinese that if they are to move from global power to global leadership, they need to adopt more liberal global norms?

Simply to pose the questions is to invite a negative answer. Britain is no longer big enough to effect major change through a series of bilateral relationships. This may even be true with small and middle-sized countries like say Vietnam. Relatively speaking, we may have more leverage, but they too are tied in to regional organisations and power structures – Associate of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China in the case of Vietnam.

In other words, given the UK’s place in the world the way to make Britain safer and more stable is to contribute to the development of a safer and more secure international environment through the introduction of new norms, better international legal frameworks and institutions which do tackle at source underlying causes of power imbalances.

Furthermore, this is not just a question of relations between nation states: it is also about preventing a big beast jungle where private actors – banks, new technology firms, extractive industries – ride roughshod over countries and their citizens.

It is important to have a positive and proactive stance in order to avoid foreign policy descending into endlessly reactive crisis management.

What are the levers we can pull and the resources we can bring to bear to achieve our aims?

The UK has significant resources - it is the fifth largest economy in the world. Our ranking is projected to fall to 10th in 2050, but we’ll still be a wealthy country in the top quartile.

We have considerable military strength. The UK has the largest military budget in the EU, has a navy bigger than the French, Italian and German Navies combined – and possesses the fifth largest military stockpile of nuclear warheads.[11] There is an argument to be had about whether we devote too much or too little resource to our military and what the balance should be between conventional, nuclear and cyber resources. For the purposes of this analysis I am going to assume a steady state.

Our soft power is remarkable, and our history has given us positional power in key institutions: permanent member of the UN Security Council; executive directorships in the IMF and IBRD; a key role for the Governor of the Bank of England in the Bank for International Settlements.

We also have strong alliances through NATO and the Anglosphere. The Joint Intelligence Committee (on which I served in humble capacity as a junior civil servant during the 1983 Iran-Iraq War) still relies on shared intelligence with the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia and the UK.

Perhaps the most important is the English language – spoken by approximately 20 per cent of the world’s population.[12] World class universities such as Oxford, Cambridge and the London universities attract students from across the world. The UK has renowned cultural resources and media influence through the BBC World Service.

Under Labour, some sources of soft power were enhanced significantly and consequently we are well respected for our overseas aid programme, our debt forgiveness initiative and climate change leadership. We have a large and highly regarded diplomatic service, the power of connectivity and the network of Commonwealth nations.

But our history is also a liability. Almost every former colony has resentments as well as warm memories. The tension between this chequered colonial past and how we move beyond it is played out in unusual context: the Commonwealth.

For some, the Commonwealth will never be able to shake off its colonial roots and is therefore dismissed as a relic that is not fit for modern times. Others see such criticism as unfair and argue that the Commonwealth is a very different institution to what it was in the 1970s. The Commonwealth gives us an opportunity to express what Lord Rickets called “convening power”[13]. The Commonwealth consists of 53 countries and contains 2.4 billion people[14] – one third of the earth’s population – of which more than 60 per cent are under the age of 29. As of 2017, the combined GDP of the Commonwealth was US$10.4 trillion and bilateral intra-Commonwealth trading costs are on average 19 per cent less than those between non-member countries.[15] The Commonwealth boasts five G20 economies (Australia, Canada, India, South Africa and the UK) and four out of five of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance are Commonwealth Members (Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK). And of course, members of the Commonwealth club also populate the other major international institutions, such as the UN General Assembly.

The Commonwealth Charter lists human rights, international peace and security, democracy, sustainable development and gender equality as among its core values. While it certainly has its limitations and baggage, if approached as an equal and voluntary association of states rather than a post-colonial toy, the Commonwealth’s vast network and sheer size can act an important network within which we can build progressive alliances and networks.

Conclusion

In this environment, the idea of Global Britain – a Britain reaching out across the world to influence events seems to be a throwback to the 1950s – an idea constructed on the fantasy of England as a seafaring nation almost entirely for the backward-looking domestic audience whose support the Government fears losing to Nigel Farage.

Instead I think we should start a grown-up discussion about the modernisation of international institutions to tackle 21st Century problems. These are inherently shared and they are not amenable to national solutions. The current framework is biased towards protecting free trade and financial investments at the expense of people and the environment.

These are the items I would put at the top of the agenda:

Building international institutions takes time and it is a shared enterprise. But we should be inspired by the example of those who went to Bretton Woods in 1944 before WWII was over. It is never too soon to begin. Let us not leave it until it’s too late.

The views expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or position of the Foreign Policy Centre. The essay was developed from a speech given at the In Defence of Multilateralism event with Helen Goodman MP, Lord Ricketts, Dr Marina Prentoulis and Steve Bloomfield. This was part of an occasional series exploring Britain’s role in the world and follows on from the Global Britain: Myths, Reality and Post-Brexit Foreign Policy event with Rt Hon John Whittingdale MP, Dr Judi Atkins, Dr Andrew Glencross and Henry Mance earlier this year.

Photo by Rob, published under Creative Commons with changes made.

[1] The World Bank, The World Bank in China, April 2019, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview#1

[2] Agencies, 10 facts about BRICS, South China Morning Post, September 2017, https://www.scmp.com/news/world/article/2109490/10-facts-about-brics

[3] Human Development Reports, Human Development Data (1990-2017), UNDP, http://hdr.undp.org/en/data#

[4] The World Bank, Decline of Global Extreme Poverty Continues but Has Slowed: World Bank, September 2018, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/09/19/decline-of-global-extreme-poverty-continues-but-has-slowed-world-bank

[5] UNHCR UK, Worldwide displacement tops 70 million, UN Refugee Chief urges greater solidarity in response, June 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/uk/news/press/2019/6/5d03b22b4/worldwide-displacement-tops-70-million-un-refugee-chief-urges-greater-solidarity.html

[6] Amnesty International, Amnesty International Annual Report 2017/18, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2018/02/annual-report-201718/

[7] Transparency International, Corruption weakens democracy, January 2019, https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/cpi_2018_global_analysis

[8] PwC, The World in 2050 – The Long View: How will the global economic order change by 2050?, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/economy/the-world-in-2050.html

[9] BBC Politics, Jeremy Corbyn: Labour leader’s speech, BBC, September 2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/live/uk-politics-45653499

[10] Jess Gifkins, Samuel Jarvis and Jason Ralph, ‘Global Britain in the United Nations’ (United Nations Association-UK, 2019)

[11] Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American scientists, May 2019, https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/

[12] Dylan Lyons, How Many People Speak English, And Where Is It Spoken?, Babbel Magazine, July 2017, https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/how-many-people-speak-english-and-where-is-it-spoken/

[13] The Foreign Policy Centre, In Defence of Multilateralism, SoundCloud, July 2019, https://soundcloud.com/foreign-policy-centre/in-defence-of-multilateralism

[14] Commonwealth Secretariat, Fast Facts on the Commonwealth, The Commonwealth, February 2019, http://thecommonwealth.org/fastfacts

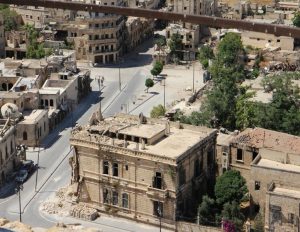

[post_title] => FPC Briefing: In Defence of Multilateralism [post_excerpt] => [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => fpc-briefing-in-defence-of-multilateralism [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2019-09-24 11:01:15 [post_modified_gmt] => 2019-09-24 11:01:15 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://fpc.org.uk/?p=3935 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [2] => WP_Post Object ( [ID] => 3938 [post_author] => 38 [post_date] => 2019-07-23 16:23:43 [post_date_gmt] => 2019-07-23 16:23:43 [post_content] =>The seizure of U.K. flagged tanker Stena Imperio by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps in the Strait of Hormuz in apparent retaliation for Gibraltar’s detention of Grace 1 has unsurprisingly given rise to considerable press reaction. A recurrent theme in news reports is whether the action taken by Gibraltar was legal. Some press reports suggest that the Governments of Gibraltar and the UK were lured into action by the US and have been co-opted into supporting President Trump’s desire to put further pressure on Iran’s economy by squeezing Iranian oil exports. While it may be the case that the US provided the intelligence about the movements and cargo of Grace 1, the Government of Gibraltar was quick to state that there had been “no political request at any time from any Government” to act and that the detention was made “as a direct result only of the Government having reasonable grounds to believe that the vessel was acting in breach of established EU sanctions against Syria”.[1]

So was the detention of Grace 1 legal?

There has been a suggestion that the detention was not legal because the vessel was not owned or controlled by EU persons and because the EU doesn’t impose its sanctions on others outside the Union. However, a closer look at the legislation involved shows that there was a legal basis for the detention and that the origins of that legislation were put in place as early as March this year.

First, in March 2019 Gibraltar enacted the Sanctions Act 2019. That Act provides at Article 6(1) for the automatic recognition and enforcement of ‘international sanctions’. ‘International sanctions’ is defined to include, amongst others, UN sanctions; EU sanctions; and, various restrictive measures imposed by UK.[2] It was intended, according to a newsletter published by The National Coordinator for Anti-Money Laundering and the Combatting of Terrorist Financing of the Government of Gibraltar in April 2019, to ensure that any restrictive measures imposed by both the EU and UK will have effect without the need for further implementing legislation and specifically refers to restrictive measures that may be imposed by the UK under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 .[3]

Subsequently on the 3rd July Gibraltar published the Sanctions Regulations 2019 which specifically give power to the Chief Minister, under Article 5(3) (a), to designate a ship as a ‘Specified Ship’ and to then detain it where the Chief Minister ‘has reasonable grounds to suspect that the ship he has designated in the Notice as a Specified Ship is, has been, or is likely to be, involved in a breach of the EU Regulation…..’.[4] The EU Regulation in question is defined to be EU Regulation No. 36 of 2012 as amended (the ‘EU Syrian sanctions’) which sets out the EU’s restrictive measures against Syria.[5]

Pursuant to EU Syrian Sanctions a number of Syrian persons and entities were listed as designated including, Baniyas Refinery in Syria which was listed in 2014. The intelligence provided to the Government of Gibraltar indicated that Grace 1 was heading to Baniyas Refinery with a full cargo of oil.

The next question that arises is on what basis it can be said that the EU sanctions would have been breached where there was no obvious EU connection in terms of the vessel’s owners or flag state? The answer to that can be found in the EU Syrian sanctions which, like most EU restrictive measures, sets out their scope.

The EU Syrian sanctions apply: [6]

(a) within the territory of the Union, including its airspace;

(b) on board any aircraft or vessel under the jurisdiction of a Member State;

(c) to any natural person inside or outside the territory of the Union who is a national of a Member State;

(d) to any legal person, entity or body, inside or outside the territory of the Union, which is incorporated or constituted under the law of a Member State;

(e) to any legal person, entity or body in respect of any business done in whole or in part within the Union.

While the precise background to the detention has not been explained by the Government of Gibraltar, subsection (e) is very broad. It applies to ‘any person, entity or body’. There is no requirement here that it must be an EU person or entity. It applies ‘in respect of any business’, again this is very wide – shipment of goods is no doubt a type of business that is covered. Finally, it applies where that business is ‘done in whole or in part within the Union’ and as such, a shipment carrying goods to a designated entity would only have to pass through EU waters to be caught. Against this background, Grace 1 loaded with cargo on her way to a designated refinery in Syria would fall within EU sanctions jurisdiction once she entered EU waters.

Under the Sanctions Regulations 2019 a Specified Ship ‘must be detained if it is in BGTW (British Gibralter Territorial Waters);’ and ‘may not leave BGTW unless permitted to do so by an order of the court or where the notice designating the ship as a Specified Ship has been revoked’. It would therefore appear that there was a legal basis for the detention and the Sanctions Regulations 2019 specifically give the Government of Gibraltar power to detain vessels suspected of being involved, or likely to be involved, in breaching the EU Syrian sanctions.

The power to detain vessels given by the Gibraltarian regulations are in contrast to the usual penalties applicable for a breach of EU sanctions. Pursuant to the EU Syrian sanctions, each Member State is required to lay down the penalties that are applicable for breach of the restrictive measures which must be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive”. The penalties vary from Member State to Member State. In the UK, there is a civil penalty regime administered by the UK Treasury’s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) that gives a scale of penalties of up to £1 million or 50% of the breach, whichever is higher and/or there can be criminal fines or imprisonment. There is currently no power under the UK’s (or other Member States’) Syrian sanctions implementing legislation to detain vessels, however, the UK’s Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act which was passed in May 2018 gave the UK Government power to make sanctions regulations including shipping sanctions.[7] Pursuant to that Act, the UK’s Syrian (Sanctions)(EU Exit) Regulations 2019 were laid before Parliament on 5 April which will take effect after the UK leaves the EU will give power to maritime enforcement officers in certain circumstances to stop and board a ship if the officer has ‘reasonable grounds to suspect that a relevant ship is carrying prohibited goods or relevant goods’.[8]

The crew of Stena Imperio and their families will take little comfort from the fact that there appears to have been a legal basis for the detention of Grace 1. They and many others will no doubt continue to question the political decision-making that lead to the detention given the inherent risk it posed to UK shipping.

Michelle Linderman is a partner at Crowell & Moring’s International Trade Group, in the firm’s London office. An English qualified solicitor with over 20 years of experience, Michelle advises clients – such as international businesses, traders, ship owners, charterers, insurers, financial institutions, and energy companies – on U.K.-specific and cross-border sanctions, including matters that concern national and international trade and financial sanctions. Before joining Crowell & Moring, Michelle was a partner and the Global Head of Sanctions at Ince & Co’s London office. She was seconded to Ince & Co's Hong Kong office from 2001 to 2004.

[1] Rock Radio, Chief Minister’s statement to Parliament regarding Grace 1, July 2019, https://www.rockradio.gi/local/local-news/chief-ministers-statement-to-parliament-regarding-grace-1/

[2] Gibraltar Laws, Sanctions Act 2019, March 2019, https://www.gibraltarlaws.gov.gi/articles/2019-06o.pdf

[3] Newsletter of The National Coordinator for Anti-Money Laundering and the Combatting of Terrorist Financing of the Government of Gibraltar, April 2019, http://www.gfsc.gi/uploads/NCO%20Sanctions%20Act%202019%20Newsletter.pdf

[4] Gibraltar Laws, Sanctions Regulations 2019, July 2019, https://www.gibraltarlaws.gov.gi/articles/2019s131.pdf

[5] Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011, Official Journal of the European Union, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2012:016:0001:0032:EN:PDF

[6] Ibid. [See Article 35]

[7] UK Government, The Syria (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2019/792/regulation/90/made

[8] Ibid.

[post_title] => Seizure of Stena Imperio by Iran raises questions about legality of Gibraltar’s detention of Grace 1 [post_excerpt] => [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => seizure-of-stena-imperio-by-iran-raises-questions-about-legality-of-gibraltars-detention-of-grace-1 [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2019-07-24 12:31:22 [post_modified_gmt] => 2019-07-24 12:31:22 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://fpc.org.uk/?p=3938 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 7 [filter] => raw ) [3] => WP_Post Object ( [ID] => 3867 [post_author] => 38 [post_date] => 2019-07-12 10:15:12 [post_date_gmt] => 2019-07-12 10:15:12 [post_content] =>On June 5th 2019 in Turkmenistan’s capital Ashgabat, dozens of people lined up outside a state store where they heard there was sugar for sale.[1] Four years ago, there were no lines outside state stores. Now there are lines for almost everything, and it is worse outside the capital.

The folly of depending on exports of natural gas for revenues is evident now in Turkmenistan, though it has not stopped the government from its profligate spending on projects that seem to be of little, if any, value to the people of the country. The people of Turkmenistan increasingly bear the burden of trying to keep the regime of President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov financially afloat, awhile they live through the worst period in Turkmenistan’s nearly 28 years as an independent country. Alongside the decreases in the standards of living, Turkmenistan’s people face increases in restrictions.

The price of natural gas in 2014 averaged about US $350 per 1,000 cubic metres. By 2016, the price was closer to US $200. Turkmenistan’s system is opaque and such figures, which the state provides, are often suspect. It is believed between 70 and 80 per cent of Turkmenistan’s revenue comes from the sale of natural gas. Turkmenistan lost Russia as a customer at the start of 2016, and Iran as a customer at the start of 2017, leaving China as the only country currently purchasing any large volumes of Turkmen gas.

Toward the end of 2016, information started leaking out of Turkmenistan, suggesting shortages of basic food items in some areas of the country. In September 2016, in the northern Dashoguz Province there was a shortage of flour. Of nine districts in the province, only one (Gorogly district) had flour and that was at the flour mill.[2] More than one million people live in Dashoguz Province, some residing 200 kilometres from the Gorogly district. One Dashoguz resident said the line outside the flour plant was “so long it can take three to five days. People sleep in front of the mill“.[3] There was a limit of one 50-kilogram sack of flour per family, but the price at the mill was about 50 manat (a bit more than US $14) while the other option, flour from neighbouring Kazakhstan, cost 190 manat (more than US $50). By December, there were reports many state stores in Dashoguz were short of sugar and cooking oil. People wishing to purchase such items often had to put their names on waiting lists, and the wait could be as long as four to five weeks.[4]

In December 2017, high quality flour had practically disappeared from many parts of Turkmenistan. In Ashgabat, and in the Mary and Lebap provinces, the price had reportedly risen from 50 manat per sack of flour to 100 manat.[5] In February 2018, people seeking to purchase bread in Dashoguz were reportedly required to prove they had paid their gas and electric bills.[6] By the end of that month flour was being rationed to one five-kilogram sack per customer in Dashoguz. In Mary Province flour was limited to one sack (still 50 kilograms) per family and it had to be pre-ordered.[7] Even in Ashgabat, there was a limit of one one-kilogram bag of flour and a half kilogram of sugar per customer. It had previously been five kilograms of flour and one kilogram of sugar per customer.[8] In November 2018, the Hronika Turkmenistana website posted a video, said to be filmed in Ashgabat, showing people waiting for a bread truck to arrive at the local state store and being limited to no more than two loaves of bread (the flat bread that Turkmen call ‘chorek’).[9] Despite a report from a television channel in Kazakhstan that said Turkmenistan had imported some 100,000 tons of grain from Kazakhstan.[10]

Goods such as sugar, flour, and cooking oil are available at private stores and at bazaars, but the price can be anywhere from three to 10 times what it would be at a state store, so many people chose to wait. There were reports in October 2018 that people from the regions were coming to Ashgabat hoping to buy bread, flour, and cooking oil and that police were stopping and inspecting cars with license plates from the regions looking for food. Those caught taking food out of Ashgabat were fined.[11] It became increasingly difficult to enter Ashgabat. By February 2019, vehicles from the regions were forced to halt anywhere from five to 25 kilometres outside Ashgabat’s city limits.[12]

Money, actual cash, is in short supply in Turkmenistan. The government attempted to make Turkmenistan a cashless country by issuing bank cards to citizens and directly depositing salaries, pensions, and other social benefit payments into bank accounts. But many stores still do not have the necessary machines to accept card payments. Bazaars certainly are not set up for accepting bank cards. So, people take money out of automated teller machines (ATMs). These ATMs are not regularly stocked with cash, especially in the regions. When an ATM is replenished, word quickly spreads and lines form, everybody hoping the machine will still have cash when their turn comes to make a withdrawal. Security forces and police often watch lines outsides banks now since scuffles have broken out in lines and, on occasions, people have complained loudly about the government and the president.[13] Even when there is money, there are limits as to the amount of cash that can be withdrawn. Exchange bureaus in Turkmenistan stopped selling hard foreign currency in January 2016.[14] The rate of the manat on the black market at that time was between 4 to 4.2 manat to US $1. The official rate was and remains 3.5 manat to U.S. $1, but as of the start of June 2019, the black market rate is between 18.5 to 19 manat to US $1.

Unemployment is high. Turkmen authorities have never released figures for unemployment, but it is estimated 60 to 70 per cent of the eligible workforce is unemployed or underemployed. The last four years have seen layoffs in almost every sector of the country, from state employees to workers in the key gas and oil industry.

Turkmen authorities have gradually tightened restrictions for those wishing to fly out of Turkmenistan. In April 2018, there were reports authorities at the Ashgabat airport, the only airport in Turkmenistan with international flights, were preventing people under 30 years of age from boarding international flights.[15] By late June 2018, the age restriction had reportedly increased to people under 40.[16]

Women’s rights have diminished since 2016. In October 2016, women were forbidden from buying cigarettes. This restriction was eased into force in Turkmenbashi City so only women with notes from doctors saying they were addicted to tobacco could purchase cigarettes.[17] In May 2018, a dress code was introduced for non-Turkmen women in Ashgabat, obligating them to wear traditional long Turkmen dresses. Later a ban on miniskirts was introduced.[18] In February 2019, there were reports police in Ashgabat were confiscating drivers’ licenses from women.[19] And in June 2019, there was a report authorities were refusing to renew the expired drivers’ licenses of women.[20]

Students studying abroad are required to return to Turkmenistan during school breaks. Also, when they are studying abroad students from Turkmenistan have limited access to funding from home. In July 2017, parents back in Turkmenistan were limited to sending only 1,050 manat (US $300 at the official rate) per month through Western Union.[21] Some Turkmen students in Belarus, Russia, Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan were forced to withdraw from universities because they did not receive money in time to pay tuition.[22]

Allotments of water, gas, and electricity that the government has provided for free to the population since shortly after independence, were reduced starting in 2017, then totally canceled at the start of 2019. Residents were expected to pay for the installation of metres to measure their household usage of gas and water. The cost of sending children to kindergarten has also increased. In October 2017, the cost of kindergarten in Dashoguz increased from eight to 80 manat per month, with increases across Turkmenistan.[23] A group of outraged mothers went to the city administration building to complain, an act that just a few years ago would have been unthinkable. The special police unit OMON was called to the scene. The deputy head of municipal education came out and told the women he could not do anything for them, and recommended they take their concerns to the mayor’s office, which they did. Later the same day, the deputy education head was arrested and charged with calling for an overthrow of the government.[24]

To listen to Berdimuhamedov and state media, one would get the impression Turkmenistan was a paradise, the envy of countries around the world. Despite a deepening economic crisis with the accompanying shortages affecting the country’s people so much, Turkmen authorities continued spending money on projects of questionable benefit.

In December 2010, Turkmenistan was chosen to host the 2017 Asian Indoor Martial Arts Games (AIMAG). When Turkmenistan was selected as the AIMAG host, the country was exporting gas to Russia, Iran, and had just completed two (of four planned) gas pipelines to China. Gas prices were rising on global markets. By 2015, gas was half the 2010 price. Authorities had approved construction of a US $2.3 billion airport outside Ashgabat for AIMAG. The cost of construction for the AIMAG facilities, including a circular five-kilometre monorail system, was estimated at more than US $5 billion. As gas revenues fell, the government started garnishing workers’ wages as ‘voluntary donations’ for AIMAG.[25] Non-residents of Ashgabat, many of whom had been there to help build the AIMAG facilities, were chased from Ashgabat before the games opened on September 17th, 2017. Thousands of citizens were organised as volunteers to help with AIMAG or as spectators to keep event halls full so that media coverage, especially foreign media, showed images of packed stadiums and indoor gyms.

20 days after AIMAG ended, Turkmenistan’s first golf course opened in Ashgabat, despite the fact few in Turkmenistan know anything about the game, and Turkmenistan is nearly 90 per cent covered by desert, so water is scarce. In May 2018, the Caspian port in Turkmenbashi City reopened after US $1.5 billion in renovation and modernization work. In July 2018, Turkmen authorities announced the completion of a 170-hectare artificial island in the shape of a crescent off Turkmenistan’s Caspian coast.[26]

When state media is not boasting about these achievements, it often covers President Berdimuhamedov’s exploits. Berdimuhamedov claims to have authored more than 40 books on topics ranging from tea to the native Akhal Teke horse, as well as books such as ‘Arkadag’s Doctrine. The basis for health and inspiration.’ State television shows Berdimuhamedov riding bicycles, horses, lifting weights, playing guitar or piano, singing songs, etc., sometimes with his grandsons. Among state television’s recent favourites are clips showing the president twisting and turning expensive automobiles around racetracks and in the desert, or dressing in military fatigues to participate in military drills, and sometimes demonstrating how to fire weapons and throw knives.[27]

Small wonder some of Turkmenistan’s citizens

have chosen to leave the country. According to a recent report, some 1.9

million people, more than one-third of Turkmenistan’s population, might have

already left in the last decade.[28]

It is difficult to know if this is true. Turkmenistan never released the

results of its last census in 2009. But it is known that many thousands of

Turkmenistan’s citizens have left for Turkey, Cyprus, Russia, and other

countries looking for work and they have not returned to Turkmenistan.

[1] Radio Azatlyk, В Ашхабаде продолжается дефицит продуктов, сохраняются очереди за сахаром (The deficit of products continues in Ashgabat, the lines for sugar are still there), Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 2019, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29982598.html

[2] Qishloq Ovozi, Turkmenistan’s Reality: Unpaid Wages And Shortages Of Food, RFE/RL, September 2016, https://www.rferl.org/a/turkmenistan-reality-unpaid-wages-food-shortages/28016347.html

[3] Ibid.

[4] Qishloq Ovozi, On The Waiting List For Sugar, Cooking Oil In Turkmenistan, RFE/RL, December 2016, https://www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-waiting-list-for-sugar-cooking-oil/28154447.html

[5] Radio Azatlyk, В Туркменистане наблюдается дефицит муки (Turkmenistan is witnessing a flour shortage), RFE/RL, December 2017, https://rus.azattyq.org/a/28894201.html

[6] Radio Azatlyk, В Туркменистане для покупки муки требуют справку об отсутствии задолжности за газ и электричество (To purchase bread in Turkmenistan one must bring a form showing they have no debts for gas and electricity), RFE/RL, February 2018, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29043406.html

[7] Radio Azatlyk, В Дашогузе на одного взрослого члена семьи можно купить 5 килограмм муки, а в Мары нужно отстоять долгую очередь (In Dashoguz one adult family member can purchase 5 kilogram of flour, and in Mary one must wait in long lines), RFE/RL, February 2018, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29063701.html

[8] Туркменистан: Продовольственный кризис добрался до столицы (Food crisis reaches the capital), Turkmen.news (formerly the Alternative News of Turkmenistan), March 2018, https://habartm.org/archives/8729

[9] В Ашхабаде по-прежнему наблюдаются очереди за хлебом (As previously, there are queues in Ashgabat for bread), Hronika Turkmenistana, November 2018, https://www.hronikatm.com/2018/11/v-ashhabade-po-prezhnemu-nablyudayutsya-ocheredi-za-hlebom/

[10] Казахстан отправил на экспорт более 5 млн тонн зерна (Kazakhstan exported more than 5 million tonnes of grain), Khabar 24 TV, September 2018, https://24.kz/ru/news/economyc/item/264623-kazakhstan-otpravil-na-eksport-bolee-5-mln-tonn-zerna

[11] Полицейские штрафуют водителей за вывоз продуктов из Ашхабада в регионы (Police are fining drivers for taking food from Ashgabat to the regions), Hronika Turkmenistana, October 2018, https://www.hronikatm.com/2018/10/politseyskie-shtrafuyut-voditeley-za-vyivoz-produktov-iz-ashhabada-v-regionyi/

[12] В Ашхабад по-прежнему не пропускают машины из регионов (They are still not allowing vehicles from regions into Ashgabat), Hronika Turkmenistana, February 2019, https://www.hronikatm.com/2019/02/ashhabad-po-prezhnemu-zakryt-dlya-inogorodnego-transporta/

[13] Qishloq Ovozi, The Sights And Sounds Of Discontent In Turkmenistan, RFE/RL, October 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/the-sights-and-sounds-of-discontent-in-turkmenistan/29555377.html

[14] Olzhas Auyezov, Turkmenistan exchange bureaus stop selling foreign currency, Reuters, January 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/turkmenistan-forex/turkmenistan-exchange-bureaus-stop-selling-foreign-currency-idUSL8N14W2XY20160112

[15] В Туркменистане с международных рейсов снимают молодых людей (Young people are being taken off international flights in Turkmenistan), Hronika Turkmenistana, April 2018, https://www.hronikatm.com/2018/04/v-turkmenistane-s-mezhdunarodnyih-reysov-snimayut-molodyih-lyudey/

[16] Radio Azatlyk, Из Туркменистана не выпускают граждан моложе 40 лет (They are not allowing people under 40 to leave Turkmenistan), RFE/RL, June 2018, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29323179.html

[17] Туркменбаши: Женщинам продают сигареты по справке из наркологии (Turkmenbashi: Cigarettes are sold to women if they have a note from narcology), Alternative News of Turkmenistan, January 2017, https://habartm.org/archives/6282

[18] Radio Azatlyk, В Ашхабаде от женщин не туркменской национальности требуют носить длинные платья. (In Ashgabat women who are not of Turkmen nationality are required to wear long dresses), RFE/RL, May 2018, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29261043.html

[19] Radio Azatlyk, Ашхабадская полиция отбирает водительские права у женщин (Ashgabat police confiscating drivers’ licenses from women), RFE/RL, February 2019, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29776458.html

[20] Radio Azatlyk, В Туркменистане женщинам не продлевают водительские удостоверения (They are not prolonging drivers’ licenses for women), RFE/RL, June 2019, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29978517.html

[21] В Туркменистане выстраиваются очереди из желающих перевести деньги за рубеж (In Turkmenistan lines are forming for those wishing to send money abroad), Hronika Turkmenistana, July 2017, http://www.chrono-tm.org/2017/07/v-turkmenistane-vyistraivayutsya-ogromnyie-ocheredi-iz-zhelayushhih-perevesti-dengi-za-rubezh-2/

[22] Azatlyk, Родители студентов, отчисленных из-за неуплаты по вине туркменских банков, не могут вернуть свои деньги (Parents of students who were expelled for not paying tuition because of Turkmen banks cannot get their money back), RFE/RL, July 2018, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29360779.html

[23] Radio Azatlyk, В Дашогузе 10-кратное увеличение оплаты детсада вызвало стихийную акцию протеста. (A 10-time increase in the cost for kindergarten sparks spontaneous action), RFE/RL, October 2017, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/28791955.html

[24] Radio Azatlyk, После протеста против повышения оплаты детского сада чиновника в Дашогузе обвиняют в «призыве к восстанию против власти» (After the protest against the increase in fees for kindergarten, an official is charged with “calling for the overthrow of the government”), RFE/RL, October 2017, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/28802325.html

[25] Qishloq Ovozi, Milking Turkmenistan's People To Pay For The Games, RFE/RL, March 2017, https://www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-milking-turkmen-people-pay-for-games/28403657.html

[26] Turkmenistan creates artificial island near Caspian coast, Trend, July 2018, https://www.azernews.az/region/134953.html

[27] Президент Туркменистана принял участие в военных учениях (The president of Turkmenistan took part in military exercises), Hronika Turkmenistana, August 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OtLxYyf8K8I

[28] Radio Azatlyk, Источник: За 10 лет из Туркменистана выехало почти 1,9 миллиона человек (Source: During the last 10 years almost 1.9 million people have left Turkmenistan), RFE/RL, May 2019, https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29969698.html

[post_title] => Food lines in a land of marble [post_excerpt] => [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => food-lines-in-a-land-of-marble [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2019-07-14 15:26:04 [post_modified_gmt] => 2019-07-14 15:26:04 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://fpc.org.uk/?p=3867 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 8 [filter] => raw ) [4] => WP_Post Object ( [ID] => 3872 [post_author] => 38 [post_date] => 2019-07-12 10:10:06 [post_date_gmt] => 2019-07-12 10:10:06 [post_content] =>Turkmenistan is a complex and opaque destination for investment. The business climate is characterised by structural economic problems and general economic mismanagement, with the prioritisation of vanity projects over core investment and a near-total absence of checks and balances on presidential decision-making. This facilitates endemic corruption and the influence of opaque but powerful vested interests over all aspects of the economy and business environment.

All talk

Turkmenistan’s economy has undergone few structural reforms since independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. It retains key hallmarks of the post-Soviet economy, remaining overwhelmingly dependent on the oil and gas sector for growth. The Turkmenistan authorities regularly express their desire to drive economic growth and diversification through foreign investment. Since the economic slowdown began in late 2014, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov has courted multiple countries, especially a number of Middle East and Gulf states, with offers of economic co-operation.

However, such statements can mostly and fairly be assessed as hollow platitudes. The vast majority of the economy remains firmly in the hands of either the state, or those of opaque companies that are largely understood to trace their beneficial ownership back to prominent politically connected figures. While there is almost never a paper trail to confirm such links, investigative journalists, and due diligence enquiries into Turkmenistani entities, routinely find indications among human sources close to the relevant sectors of companies’ beneficial ownership tracing back to prominent individuals, often in the president’s family.[1] There is a distinct lack of will at the highest political level to facilitate foreign investment in an indiscriminate manner, given the competition that this is perceived to pose to the carefully controlled division of state assets and economic sectors among a select few people close to the political centre.

This aversion to opening up the economy is evidenced by the fact that the period since the downturn that began in late 2014 has been accompanied by no improvement in the multitude of informal barriers to existing and new investment activity. The major structural impediments to a transparent, fair and competitive business environment remain firmly in place.

Protectionist instincts

There are relatively few formal barriers to foreign investment activity. However, those that exist markedly affect the country’s most prominent and attractive sector for overseas investment activity, oil and gas. Turkmenistan’s long-standing policy of granting only service contracts to foreign companies for major onshore gas projects is the main example of this approach. More commercially attractive production-sharing agreements (PSAs) are almost always granted only for offshore field development. The only company to have secured an onshore PSA for a major gas field (in 2007) is the state-owned Chinese company China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). Two European companies have PSAs for onshore oil fields, but these are minor reserves in the country’s west and represent an anomaly in the broader policy of not granting such contracts.

The authorities have made no move whatsoever towards relaxing these restrictions in the past few years, despite the fact that it is probably the most obvious way to drive fresh investment and counter the lost revenue from the economic slowdown and loss of key gas export contracts (with the loss of Russia and Iran as customers) since 2015. Instead, the authorities when facing increasing pressure on budget revenues and macro-economic stability show a tendency towards reinforcing protectionist instincts.

Vested interests and informal requirements create risks for investors

The handful of laws that set out the terms under which foreign companies can enter into joint ventures with the state are relatively clear and well drafted. However, the top-down nature of decision-making means that legislation generally is enacted without consultation or any formal parliamentary oversight. Its enforcement is highly irregular, and a range of informal practices trump legal provisions.

Perhaps the best example of this is the enormous informal power understood to be wielded by an opaque body known as the Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (UIE). Lawyers in the country firmly attest to the absence of any legal requirement for prospective investors to be members of – or to liaise with – the UIE to secure investment in the country, and a review of the law confirms no such requirement.

However, sources on the ground and information from foreign businesses who have approached the Turkmenistan market strongly suggests that membership of the UIE and co-ordination of prospective investment activities with its chair, the influential local businessman Alexander Dadayev, is seen as a de facto requirement in order to gain access to certain contracts or state loans, especially any state tenders. This arrangement allows Dadayev, who is understood to be close to the government and president, to control which foreign entities gain access to the economy, and to exclude them where the authorities wish to reward locally connected companies with contracts or commercial opportunities.

Corruption

Both high-level and low-level corruption are pervasive and endemic. They are likely to touch domestic and foreign business alike. The scale of the perceived extent of bribery and graft is captured in Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perceptions Index. Turkmenistan is consistently among the worst performing nations surveyed by TI globally, and the worst performing of all the former Soviet states. It has scored between 18 and 20 points since 2015, where 100 points signifies a ‘very clean’ country and 1 a ‘very corrupt’ one. Ranked against 179 other countries in 2018, Turkmenistan came 161st (where first is the country perceived to be the least corrupt).[2] These consistently poor scores highlight the entrenched nature of both high-level and low-level corruption over many years.

What does this mean for business activity? At the higher level, family ties and political loyalty are the main factors that determine the awarding of contracts. Traditionally privilege and access to commercial opportunities extended to a group of people around the president, appointed to cabinet and other senior state positions, most of whom are not direct relatives of the president. In recent years there are growing indications that Berdimuhamedov’s family are now increasingly in control of many key sectors, and that the elite circle enjoying dividends from the country’s industry is narrowing.[3] In such a climate, foreign businesses without their own nepotistic ties to prominent figures face little chance of securing a contract, regardless of their objective value to the economy or ability to service a requirement.

At a lower level, companies are likely to find that officials – even up to ministerial level – expect bribes or favours (such as employing their relatives) in return for progress with administrative decisions or the issuing of licences.